The Netflix documentary How to Change Your Mind opens with a rather unusual disclaimer: The following series is designed to entertain and inform—not provide medical advice. You should always consult your doctor when it comes to your personal health or before you start any treatment. Netflix had to put that up because the documentary, inspired by a book of the same name by Harvard professor Michael Pollan, deals with humanity’s turbulent relationship with a bunch of mind-expanding substances.

For most, that particular set of words translates into drugs. But for the medical community, things aren’t as extreme. Concoctions like LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), acid in popular culture, have had something of a strange trip over the last 80- odd years since it was discovered in a pharmaceutical lab. In the heyday of LSD research in the 1950s, it was believed that dropping acid could help the therapeutic process by facilitating deep introspection and emotional release. This even as it was a key trigger in the counterculture movement in US in the ’60s. Apple cofounder Steve Jobs once described his experiments with LSD as “one of the most important things in my life. LSD shows you that there’s another side to the coin”.

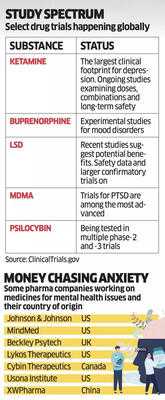

Then, in the dawn of the ’70s, it all shut down— the good and the bad. LSD came to be regarded as a criminal narcotic, dealt by dealers, dropped by dopeheads. Now, after years in the wilderness, there is serious scientific research that is making many in psychiatry sit up and take notice. The latest is a mid-stage study that came out in early September. According to it, microdosing of MM120—a pharmaceutical version of LSD created by MindMed Inc—could help ease anxiety for up to three months, showing real potential as a new way to treat one of the most common mental health issues in the world. It is early days, and much more scientific method needs to be applied to really understand the benefits and risks of microdosing, but here’s the thing.

It isn’t just LSD.

A number of substances, including psychedelics like psilocybin and mescaline, and dissociatives like ketamine, declared illegal around the world for a few decades, are going through a process of reinvention, thanks to a renewed wave of scientific inquiry. If successful, it can redefine the way some of the world’s most worrying mental health issues are treated. As Pollan, himself a believer in the power of substances like psychedelics, told ET, “Mental health crises will drive acceptance of these unconventional therapies, in large part because the conventional therapies are not working very well. Mental health professionals know it.” But for substances like pharmaceuticalLSD, the process to legal approvals will be fraught with challenges, not least among them is overcoming decades of public demonisation.

TRIP DOWN MEMORY LANE

As Pollan’s documentary on Netflix pointedly underlines, LSD was synthesised in Switzerland the same year as nuclear fission was discovered in neighbouring Germany in 1938. But unlike the unleashing of the power of the atom, LSD didn’t quite make news until much later. A few years before that, Swiss pharma major Sandoz had isolated a medicine from ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and related plants. Ergotamine ended up as a treatment for migraine. Research into ergots slowed for a some years, but chemist Albert Hofmann, a researcher at Sandoz, was intrigued enough to pick up experiments with chemical derivatives of ergot alkaloids. Building on many years of work, he synthesised the 25th derivative in a series of lysergic acid compounds, which would come to be known as LSD-25. But it wasn’t until a few years later that Hofmann stumbled onto its psychedelic effects, after absorbing a small amount through his fingertips.

Hofmann, in his report to his boss, would write, “At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterised by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours.” That was the first ever acid trip.

The initial research had happened into the compound with the intention of obtaining a circulatory and respiratory stimulant. But Sandoz was interested in its broader use cases, and to encourage more research into the compound, distributed it for free to qualified researchers and clinicians under the brand name Delysid in the early 1950s. That triggered what Pollan calls the golden age of LSD research when hundreds of studies were published, and LSD was seen as a promising tool in psychotherapy and experimental psychiatry. Eventually, from academia, LSD trickled down to artists and musicians, and then to the public. It became, in the 1960s, an important ingredient of anti-war protests, anti-establishment thinking and a rediscovery of spirituality. All of that drew government attention and, by 1966, LSD started to get banned, first in California where its usage was the highest, to the rest of US and eventually around the world.

PSYCHEDELIC RENAISSANCE

The turn of the millennium, however, saw the return of LSD— and a whole bunch of other drugs like psilocybin and MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine)—to research labs. A key trigger was the realisation that much of the world was—and still is—going through a mental health crisis.

The scale of the crisis is mind-boggling. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over a billion people are living with mental health conditions around the world, with anxiety and depressive disorders being the most common. According to its 2025 report, “suicide remains a devastating outcome, claiming an estimated 727,000 lives in 2021 alone. It is a leading cause of death among young people across all countries and socioeconomic contexts”. Then there is the economic cost—depression and anxiety alone cost the global economy an estimated $1 trillion a year. There is no silver bullet for this. Therapy can be a powerful tool in pushing back, but there are a couple of problems there, not least among them is the fact that there simply aren’t enough therapists to go around.

Technology could help, but there are as yet unanswered questions about ethics—how data is used and security and privacy concerns. The current regime of medicines, too, can help, but there are issues there as well. According to studies, about a third of patients who take these meds do not improve or show only a partial response. The academia and pharma companies in the West have reacted to the scale of the issue by dusting off some old research. That has triggered a renewed look at psychedelics in universities like Johns Hopkins, US, and Imperial College London. The MindMed trial is the latest in a long line of studies that has happened over the last decade and half in the West. David Nutt, director of the neuropsychop harmacology unit in the division of brain sciences at Imperial College London, says “there is strong public support for these drugs as medicines as modern scientific studies show the ban through the UN conventions of 1960 and 1971 was politically-, not science-driven”.

LACK OF LOCAL TRIALS

It isn’t that psychiatrists in India aren’t exploring the medical use of such substances. Ketamine treatments are offered under the guidance of doctors and therapists at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) in Bengaluru. However, beyond such isolated cases, serious research into unconventional therapies is almost always happening outside of the country. Mental health experts reckon that in terms of having clinical trials and proving the efficacy of such interventions in India, the country is significantly behind the curve.

As Vidita Vaidya, neuroscientist and professor of biological sciences at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai, points out, “While we do have ketamine-assisted therapy in India, we don’t have a progressive policy on our own clinical trials to be able to move the envelope for ourselves. We’re waiting for someone else to figure it out, and then play catch up.” Vaidya, who does preclinical experiments on the effects of psilocybin on rodents and cell cultures, finds it difficult to source even microdoses for her research. An expert in mental health, who wants to stay anonymous, points to another issue—lack of conversations in India even within the mental health community on such opportunities. These unconventional therapies, the expert says, will require therapist training as they need to be administered under clinical observation.

The lack of conversations hampers finding willing clinicians. Add to that the difficulty in getting legal permissions and the road to local clinical trials becomes even more difficult. There are provisions in India’s narcotics act that open up avenues for medical and scientific research, according to Anita Abraham, a lawyer based in Bengaluru.

The government is also mandated to set up a National Fund for Drug Abuse, which “can also be used to conduct medical research on the use of LSD in clinical medicine, including clinical psychiatry”. The big issue is the difficulty in making these provisions work from a research point of view.

RESEARCH, RESEARCH, RESEARCH

For many, the legal availability of medical marijuana in many countries nowadays is indicative of the system—and the public’s openness in trying out unconventional therapies.

Dr Ryan L Henner, psychiatrist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, says, “The data on cannabis remains cloudy for most conditions it is purported to treat, which is different from the data on many psychedelics.” While these drugs offer hope to millions, it is critical to note that these are still in early stages. These drugs also have a higher burden of proof in trials, as evidenced last year when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rejected Lykos Therapeutics’ MDMAassisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

It was supposed to be the big coming-of-age moment for unconventional drugs, but among other things, the FDA observed that the difficulty to blind these studies meant that the data was challenging to interpret. Blinding of studies is a practice to remove bias in clinical trials where participants are not told whether they are receiving a placebo or the actual drug. In the case of mind-altering MDMA, it was easy enough for participants to figure out if they received the drug or not. After FDA’s rejection, researchers engaged in psychedelic microdosing are doubling down to ensure that their studies don’t face similar issues. However, there are a couple of things that experts do warn against. As Henner underlines, a “risk for these medicines is over-emphasis on their potential benefit with inadequate acknowledgement of risks.

All interventions have risks and benefits—no exceptions. Patients and the public should be aware of these”. Experts also emphasise the importance of therapy along with such medications, and the need to always administer them in a clinical setting. Regarding the concern of many governments about the diversion of medical psychedelics into recreational use, Nutt believes that “even actual diversion is not a good reason to block appropriate medical use”. As with any new medicine, it is nearly unavoidable that when a psychedelic substance is ultimately approved for medical use on a broad scale, we will learn of either new risks or known risks that are more substantial than previously recognised. The only way to balance the good with the bad is through the scientific method. As Henner emphasises, “The ultimate potential of these medicines is tremendous and can leave people with a sense of equanimity that can be lasting, if supported with changes in worldview and behaviour.”

For most, that particular set of words translates into drugs. But for the medical community, things aren’t as extreme. Concoctions like LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide), acid in popular culture, have had something of a strange trip over the last 80- odd years since it was discovered in a pharmaceutical lab. In the heyday of LSD research in the 1950s, it was believed that dropping acid could help the therapeutic process by facilitating deep introspection and emotional release. This even as it was a key trigger in the counterculture movement in US in the ’60s. Apple cofounder Steve Jobs once described his experiments with LSD as “one of the most important things in my life. LSD shows you that there’s another side to the coin”.

Then, in the dawn of the ’70s, it all shut down— the good and the bad. LSD came to be regarded as a criminal narcotic, dealt by dealers, dropped by dopeheads. Now, after years in the wilderness, there is serious scientific research that is making many in psychiatry sit up and take notice. The latest is a mid-stage study that came out in early September. According to it, microdosing of MM120—a pharmaceutical version of LSD created by MindMed Inc—could help ease anxiety for up to three months, showing real potential as a new way to treat one of the most common mental health issues in the world. It is early days, and much more scientific method needs to be applied to really understand the benefits and risks of microdosing, but here’s the thing.

It isn’t just LSD.

A number of substances, including psychedelics like psilocybin and mescaline, and dissociatives like ketamine, declared illegal around the world for a few decades, are going through a process of reinvention, thanks to a renewed wave of scientific inquiry. If successful, it can redefine the way some of the world’s most worrying mental health issues are treated. As Pollan, himself a believer in the power of substances like psychedelics, told ET, “Mental health crises will drive acceptance of these unconventional therapies, in large part because the conventional therapies are not working very well. Mental health professionals know it.” But for substances like pharmaceuticalLSD, the process to legal approvals will be fraught with challenges, not least among them is overcoming decades of public demonisation.

TRIP DOWN MEMORY LANE

As Pollan’s documentary on Netflix pointedly underlines, LSD was synthesised in Switzerland the same year as nuclear fission was discovered in neighbouring Germany in 1938. But unlike the unleashing of the power of the atom, LSD didn’t quite make news until much later. A few years before that, Swiss pharma major Sandoz had isolated a medicine from ergot, a fungus that grows on rye and related plants. Ergotamine ended up as a treatment for migraine. Research into ergots slowed for a some years, but chemist Albert Hofmann, a researcher at Sandoz, was intrigued enough to pick up experiments with chemical derivatives of ergot alkaloids. Building on many years of work, he synthesised the 25th derivative in a series of lysergic acid compounds, which would come to be known as LSD-25. But it wasn’t until a few years later that Hofmann stumbled onto its psychedelic effects, after absorbing a small amount through his fingertips.

Hofmann, in his report to his boss, would write, “At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterised by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colours.” That was the first ever acid trip.

The initial research had happened into the compound with the intention of obtaining a circulatory and respiratory stimulant. But Sandoz was interested in its broader use cases, and to encourage more research into the compound, distributed it for free to qualified researchers and clinicians under the brand name Delysid in the early 1950s. That triggered what Pollan calls the golden age of LSD research when hundreds of studies were published, and LSD was seen as a promising tool in psychotherapy and experimental psychiatry. Eventually, from academia, LSD trickled down to artists and musicians, and then to the public. It became, in the 1960s, an important ingredient of anti-war protests, anti-establishment thinking and a rediscovery of spirituality. All of that drew government attention and, by 1966, LSD started to get banned, first in California where its usage was the highest, to the rest of US and eventually around the world.

PSYCHEDELIC RENAISSANCE

The turn of the millennium, however, saw the return of LSD— and a whole bunch of other drugs like psilocybin and MDMA (methylenedioxymethamphetamine)—to research labs. A key trigger was the realisation that much of the world was—and still is—going through a mental health crisis.

The scale of the crisis is mind-boggling. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), over a billion people are living with mental health conditions around the world, with anxiety and depressive disorders being the most common. According to its 2025 report, “suicide remains a devastating outcome, claiming an estimated 727,000 lives in 2021 alone. It is a leading cause of death among young people across all countries and socioeconomic contexts”. Then there is the economic cost—depression and anxiety alone cost the global economy an estimated $1 trillion a year. There is no silver bullet for this. Therapy can be a powerful tool in pushing back, but there are a couple of problems there, not least among them is the fact that there simply aren’t enough therapists to go around.

Technology could help, but there are as yet unanswered questions about ethics—how data is used and security and privacy concerns. The current regime of medicines, too, can help, but there are issues there as well. According to studies, about a third of patients who take these meds do not improve or show only a partial response. The academia and pharma companies in the West have reacted to the scale of the issue by dusting off some old research. That has triggered a renewed look at psychedelics in universities like Johns Hopkins, US, and Imperial College London. The MindMed trial is the latest in a long line of studies that has happened over the last decade and half in the West. David Nutt, director of the neuropsychop harmacology unit in the division of brain sciences at Imperial College London, says “there is strong public support for these drugs as medicines as modern scientific studies show the ban through the UN conventions of 1960 and 1971 was politically-, not science-driven”.

LACK OF LOCAL TRIALS

It isn’t that psychiatrists in India aren’t exploring the medical use of such substances. Ketamine treatments are offered under the guidance of doctors and therapists at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) in Bengaluru. However, beyond such isolated cases, serious research into unconventional therapies is almost always happening outside of the country. Mental health experts reckon that in terms of having clinical trials and proving the efficacy of such interventions in India, the country is significantly behind the curve.

As Vidita Vaidya, neuroscientist and professor of biological sciences at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research in Mumbai, points out, “While we do have ketamine-assisted therapy in India, we don’t have a progressive policy on our own clinical trials to be able to move the envelope for ourselves. We’re waiting for someone else to figure it out, and then play catch up.” Vaidya, who does preclinical experiments on the effects of psilocybin on rodents and cell cultures, finds it difficult to source even microdoses for her research. An expert in mental health, who wants to stay anonymous, points to another issue—lack of conversations in India even within the mental health community on such opportunities. These unconventional therapies, the expert says, will require therapist training as they need to be administered under clinical observation.

The lack of conversations hampers finding willing clinicians. Add to that the difficulty in getting legal permissions and the road to local clinical trials becomes even more difficult. There are provisions in India’s narcotics act that open up avenues for medical and scientific research, according to Anita Abraham, a lawyer based in Bengaluru.

The government is also mandated to set up a National Fund for Drug Abuse, which “can also be used to conduct medical research on the use of LSD in clinical medicine, including clinical psychiatry”. The big issue is the difficulty in making these provisions work from a research point of view.

RESEARCH, RESEARCH, RESEARCH

For many, the legal availability of medical marijuana in many countries nowadays is indicative of the system—and the public’s openness in trying out unconventional therapies.

Dr Ryan L Henner, psychiatrist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, says, “The data on cannabis remains cloudy for most conditions it is purported to treat, which is different from the data on many psychedelics.” While these drugs offer hope to millions, it is critical to note that these are still in early stages. These drugs also have a higher burden of proof in trials, as evidenced last year when the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) rejected Lykos Therapeutics’ MDMAassisted therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

It was supposed to be the big coming-of-age moment for unconventional drugs, but among other things, the FDA observed that the difficulty to blind these studies meant that the data was challenging to interpret. Blinding of studies is a practice to remove bias in clinical trials where participants are not told whether they are receiving a placebo or the actual drug. In the case of mind-altering MDMA, it was easy enough for participants to figure out if they received the drug or not. After FDA’s rejection, researchers engaged in psychedelic microdosing are doubling down to ensure that their studies don’t face similar issues. However, there are a couple of things that experts do warn against. As Henner underlines, a “risk for these medicines is over-emphasis on their potential benefit with inadequate acknowledgement of risks.

All interventions have risks and benefits—no exceptions. Patients and the public should be aware of these”. Experts also emphasise the importance of therapy along with such medications, and the need to always administer them in a clinical setting. Regarding the concern of many governments about the diversion of medical psychedelics into recreational use, Nutt believes that “even actual diversion is not a good reason to block appropriate medical use”. As with any new medicine, it is nearly unavoidable that when a psychedelic substance is ultimately approved for medical use on a broad scale, we will learn of either new risks or known risks that are more substantial than previously recognised. The only way to balance the good with the bad is through the scientific method. As Henner emphasises, “The ultimate potential of these medicines is tremendous and can leave people with a sense of equanimity that can be lasting, if supported with changes in worldview and behaviour.”

You may also like

'Swachh Shehar Jodi' launched to help 200 cities manage solid waste

Ryder Cup chaos sees heated Bryson DeChambeau and Tommy Fleetwood clash before caddie's shove

Liam Gallagher's 'real reason' for skipping Noel's all star Oasis Wembley after party

Trump deploys troops to 'war-ravaged' Democrat-led city to tackle 'domestic terrorists'

Bombay HC Rules Pre-Consultation Notice Mandatory Before Issuing Service Tax SCNs Above ₹50 Lakh